This month’s Document of the Month is from the Nick Baldwin Collection and is a brochure from the 1924 British Empire Exhibition.

The British Empire Exhibition was held on a 216-acre site at Wembley Park in London and was opened on Saint George’s Day by King George V and Queen Mary. It was designed to highlight the finest goods and produce from around the empire and to promote trade links between imperial colonies after the instability of the First World War. The sights for visitors to see included gardens, restaurants, a funfair and the ‘Never-Stop Railway’ that transported visitors around the vast venue, but the main attractions were the pavilions which were intended to represent different countries and cultures from across the empire.

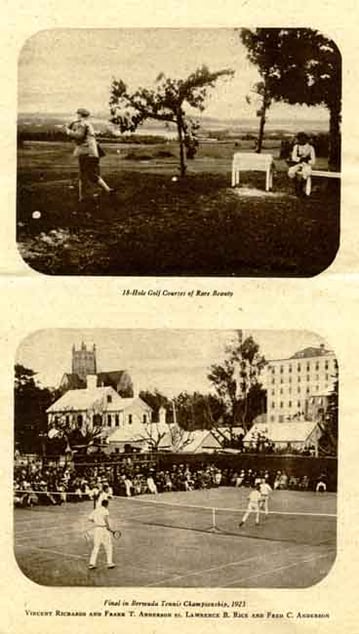

Our brochure is from the Bermuda pavilion which was created as a replica of Tom Moore’s House on Bermuda’s main island. The leaflet, which would have been handed out to visitors and potential holidaymakers in a bid to encourage British tourism and investment, explains that the series of islands were named after the Spanish explorer, Juan de Bermúdez, who first visited in the sixteenth century. It goes on to describe Bermuda’s greatest attractions for travellers including all year-round sunny weather, turquoise water, fields of flowers, and the many activities that visitors could take part in. These activities, which were typically British rather than traditionally Bermudian, included tennis, horse racing, and cricket, with the latter holding matches played by naval and club teams. Readers were told that they could travel there by steamship and that there were many hotels, boarding houses, and cottages with ‘wholesome food’ for guests, as well as ‘modern conveniences’ such as electric lights and telephones. Investment is also mentioned, with Bermuda’s harbours and docks described as ‘splendid’, and that its island location is near ‘many important trade routes’.

Our brochure is from the Bermuda pavilion which was created as a replica of Tom Moore’s House on Bermuda’s main island. The leaflet, which would have been handed out to visitors and potential holidaymakers in a bid to encourage British tourism and investment, explains that the series of islands were named after the Spanish explorer, Juan de Bermúdez, who first visited in the sixteenth century. It goes on to describe Bermuda’s greatest attractions for travellers including all year-round sunny weather, turquoise water, fields of flowers, and the many activities that visitors could take part in. These activities, which were typically British rather than traditionally Bermudian, included tennis, horse racing, and cricket, with the latter holding matches played by naval and club teams. Readers were told that they could travel there by steamship and that there were many hotels, boarding houses, and cottages with ‘wholesome food’ for guests, as well as ‘modern conveniences’ such as electric lights and telephones. Investment is also mentioned, with Bermuda’s harbours and docks described as ‘splendid’, and that its island location is near ‘many important trade routes’.

Many of the other pavilions at the exhibition were built in the local style of their respective countries. The Burmese pavilion was a copy of a teak pagoda, while the West African pavilion looked like the walled town of Zaria in Nigeria, and the Indian pavilion took its inspiration from both the Jama Masjid in Deli and the Taj Mahal. Some of the pavilions sold local merchandise for visitors to buy, like that of Hong Kong which replicated a Chinese street and sold rare gifts such as ivory carvings and silk. In the West Indies pavilion, Montserrat sold cigars, Dominica sold limes and there was a punch bar serving rum in the Jamaica area. There were even attempts at growing bananas and coffee in the accompanying tropical garden and a display of shell necklaces and other local crafts in Antigua. The organisers also wanted to demonstrate the best of British advances in technology in the Palace of Engineering which displayed the latest in transport and shipbuilding and covered thirteen acres of the exhibition ground. One of the strangest exhibits was in the Canadian pavilion and was a life size butter sculpture of the Prince of Wales and his horse housed in a giant refrigerated cabinet that represented the dairy industry of Canada. There were even concerts and shows for visitors to attend, with the Ceylon pavilion featuring a glittering exhibition of precious gemstones.

Many of the other pavilions at the exhibition were built in the local style of their respective countries. The Burmese pavilion was a copy of a teak pagoda, while the West African pavilion looked like the walled town of Zaria in Nigeria, and the Indian pavilion took its inspiration from both the Jama Masjid in Deli and the Taj Mahal. Some of the pavilions sold local merchandise for visitors to buy, like that of Hong Kong which replicated a Chinese street and sold rare gifts such as ivory carvings and silk. In the West Indies pavilion, Montserrat sold cigars, Dominica sold limes and there was a punch bar serving rum in the Jamaica area. There were even attempts at growing bananas and coffee in the accompanying tropical garden and a display of shell necklaces and other local crafts in Antigua. The organisers also wanted to demonstrate the best of British advances in technology in the Palace of Engineering which displayed the latest in transport and shipbuilding and covered thirteen acres of the exhibition ground. One of the strangest exhibits was in the Canadian pavilion and was a life size butter sculpture of the Prince of Wales and his horse housed in a giant refrigerated cabinet that represented the dairy industry of Canada. There were even concerts and shows for visitors to attend, with the Ceylon pavilion featuring a glittering exhibition of precious gemstones.

Despite many visitors, and a second opening in 1925, the exhibition actually made a loss of over a million pounds. It also proved much more controversial than previous nineteenth-century colonial fairs, particularly because people from the represented colonies were brought to the exhibition and expected to put their culture on display by dancing, singing, and entertaining the visitors while living in the pavilions for the duration of the exhibition. Those that lived off-site suffered racial discrimination from the owners of nearby hotels, with many people being refused accommodation because of their ethnicity. Waning faith in the empire and a growing sense of guilt over British imperial exploitation abroad contributed to the controversy. After Mass Observation was set up twelve years later in 1937, it was reported that people felt a ‘considerable body of guilt-feeling’ over the acquisition and administration of the empire with many having unpleasant feelings towards the words ‘Britain’ and ‘empire’. After the exhibition ended, some of the buildings were sold off and the larger surviving ones became factories, but most of them were gradually knocked down to make way for new developments. The last know remaining building, the Palace of Industry, was finally demolished in 2013.

Despite many visitors, and a second opening in 1925, the exhibition actually made a loss of over a million pounds. It also proved much more controversial than previous nineteenth-century colonial fairs, particularly because people from the represented colonies were brought to the exhibition and expected to put their culture on display by dancing, singing, and entertaining the visitors while living in the pavilions for the duration of the exhibition. Those that lived off-site suffered racial discrimination from the owners of nearby hotels, with many people being refused accommodation because of their ethnicity. Waning faith in the empire and a growing sense of guilt over British imperial exploitation abroad contributed to the controversy. After Mass Observation was set up twelve years later in 1937, it was reported that people felt a ‘considerable body of guilt-feeling’ over the acquisition and administration of the empire with many having unpleasant feelings towards the words ‘Britain’ and ‘empire’. After the exhibition ended, some of the buildings were sold off and the larger surviving ones became factories, but most of them were gradually knocked down to make way for new developments. The last know remaining building, the Palace of Industry, was finally demolished in 2013.

.png)